Making Mexican Chicago: Displacement, Gentrification and Resilience of Latinx

Dec. 3, 2024

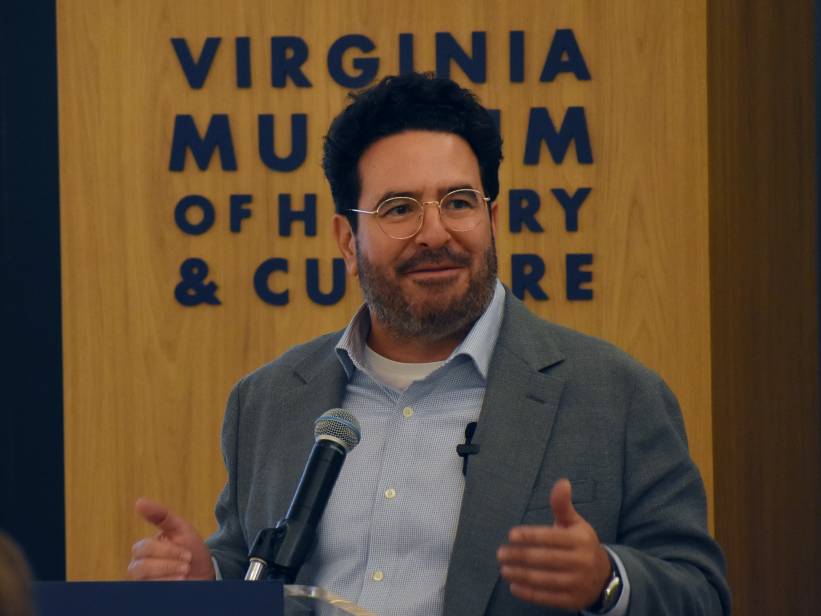

On October 22, Mike Amezcua, Associate Professor of History at Georgetown University was the guest speaker for the Greer Lecture in Latin American History. He presented his lecture, “Making Mexican Chicago: From Postwar Settlement to the Age of Gentrification.” Amezcua covered topics such as the growth of Chicago’s Mexican and Mexican-American community, its fight for housing and its battles with gentrification.

In the 1910’s and 20’s, Chicago saw an influx of Mexican immigrants fulfilling the city’s labor needs as a site of industrial capitalism. The Immigration Act of 1924 had limited the amount of European immigrants allowed into the U.S., so the U.S. turned to Mexico, wanting “cheaper, more exploitable labor.” Other Mexican immigrants left Mexico due to the instability within the aftermath of the Mexican Revolution, the lack of materialized promises of agrarian reform and religious persecution of Catholics. By the 30’s and 40’s, industries such as meatpacking and steel mills contained sizable Black and Latino workforces.

Washington D.C. promised money to cities across the nation for redevelopment in the 1950’s. Richard J. Daley, then-mayor of Chicago, wanted the federal money to redevelop the Near West Side. He planned for this community to be bulldozed and rebuilt under his plan of urban renewal. The Housing Act of 1954 stipulated that if a community were to be bulldozed, that community had to be involved in redevelopment plans for the future, and any housing that was destroyed must be replaced with new housing.

The redevelopment of these communities served as a kind of opportunity or crossroads to engage urban renewal as a civic process right to say, “We belong here and we’d like to tell the city what we envisioned as part of this renewal.” Mexican immigrant families were then included in the meetings, and many questioned why their communities needed to be bulldozed, as they believed their homes were beautiful and found demolition to be unnecessary.

“Nevertheless, some bulldozing needed to happen in this era of urban renewal to get federal money,” Amezcua said. “To combine it with state power, and to try to redevelop cities in ways that were imagined not only by the mayor, but civic boosters, the financial industry and the business sector of Chicago.”

At the same time, the expansion of a growing Mexican settlement process took place, which entails real estate. Some of the first Latina real estate agents, such as Anita Villarreal, are finding out that due to their profession, they are great spokespeople for attempting to talk to the city about saving or rehabilitating parts of the communities, not just bulldozing entirely.

Villarreal gained her real estate license in the mid 1950’s and founded her own business. Described as an “innovative pioneer,” she helped steer the displacement of Mexican residents who were being pushed out of the Near West Side and into “hostile communities.” Those communities would eventually become gem neighborhoods of Mexican Chicago, such as Pilsen.

The 1950’s saw many issues affecting Chicago: a mass deportation campaign began, targeting Mexican communities including the Near West Side. This was particularly dramatic due to the fact that urban renewal was simultaneously delineating where the bulldozer was aimed to arrive. This combination became extremely destructive and a “complete evisceration of the largest Mexicano community in the Midwest.”

In the 1960’s Chicago became a key site of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s open housing campaign, which would form part of the “Chicago Freedom Movement.” In Gage Park, part of Chicago’s southwest side, King attempted to demonstrate that African-Americans were able to buy homes in the neighborhood, even though the restrictive covenant made areas like Gage Park off-limits. King became an important figure in Chicago, putting the Southwest Side as illustrative of Northern-style segregation. The community expressed a violent backlash against King, attacking him and other marchers as they walked through the neighborhoods. This was a stark difference from how Mexicanos like Villareal were treated, who never faced any violent hostility, even as a subtle colorline was also maintained against Latinx homebuyers.

Villarreal entered the communities and offered to buy homes from White families, to then turn around and sell them to Mexican families. She promised the future of a vibrant Mexicano neighborhood in an area where White Flight was taking place. Villarreal faced backlash, but in forms of organized protests, lawsuits and boycotts of her office, as well as being barred from viewing real estate listings. Eventually, Villarreal countersued for access as a licensed real estate agent.

A real estate speculator named John Podmajersky, described by Amezcua as “one of the first gentrifiers of Pilsen,” was a previous employee of the Department of Urban Renewal. Podmajersky, and other speculators like him, turned to real estate and bought entire sections of neighborhoods in Pilsen, which he later dubbed “East Pilsen,” from Mexican families. Podmajersky bought those homes because, as he once told the press, “There’s too many people living in them, they’re old, they’re dated, they’re dangerous.” Podmajersky ended up being challenged by Mexicanos who argued that the buildings were vital resources for waves of Mexican migrants, as they served as “port of entry neighborhoods.”

In city hall, city boosters and the mayor of Chicago proposed the Pilsen River Community, under a city master plan entitled “Chicago 21,” a municipal agenda that envisioned the city in the 21st century. The goal of this plan was to house white collar workers closer to downtown and in high rises that lined the Chicago River. The Mexican community was largely against this plan, because it threatened to raze many of their buildings. They mobilized against it by creating a counter campaign called the “Anti-Chicago 21.” While Mexican Chicagoans mounted a historic campaign to resist and defeat Chicago 21, their battles against displacement through gentrification continue on today.

Today, Chicago’s Latino population lies between 29-30% of the entire city. With its large Mexican diaspora, it has been called the “second or third largest Mexican metropolis” in the U.S.